Background

November marks four years since Beijing unfurled the far-reaching 60 Decisions economic reform program in 2013. That began economic policymaking in the Xi Jinping era. This October, the president’s first term finished and a second five-year term began. We choose this midpoint to launch The China Dashboard, an appraisal of China’s economic reform progress. President Xi argued in 2013 that economic development had become unbalanced and unsustainable, and that mounting problems would dead-end China’s growth unless reforms were enacted. This diagnosis impacts not only China’s dreams of domestic prosperity but also the interests of peoples and economies worldwide whose futures are linked to China‘s outlook. Recognizing those interests in 2015, Premier Li Keqiang explicitly welcomed evaluations from abroad on China’s reform performance. The China Dashboard takes up that invitation. We look at indicators not of what Americans or international organizations think China should do, but of Beijing’s own objectives, and how much progress has been achieved so far.

Bottom Line

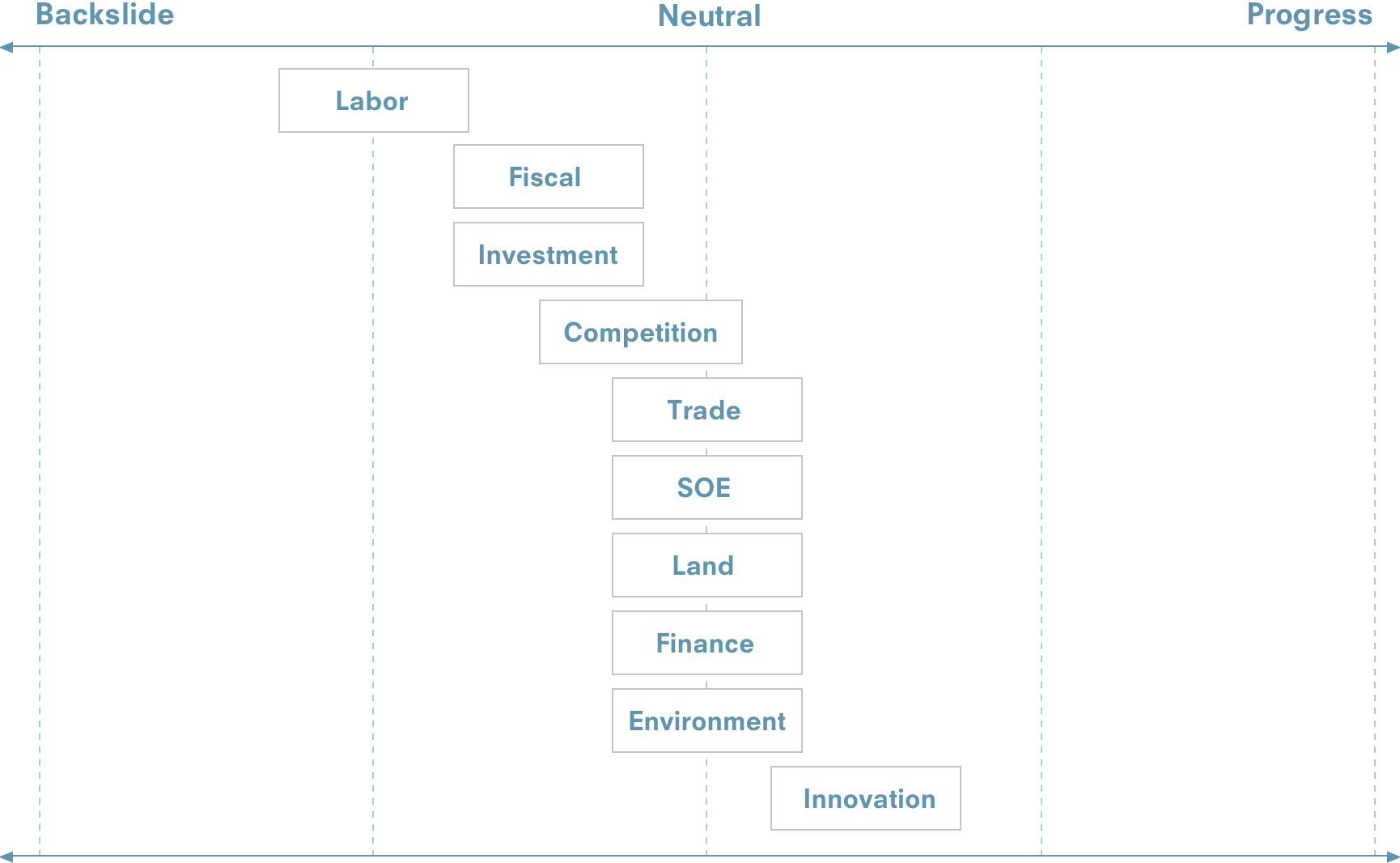

Based on data available at drafting (in most cases, through 2Q2017), China’s economic reform program remains incomplete. Indeed in many areas it appears to have stalled. There has been some progress, for example in lifting the share of innovative industries in economic output, but most objectives are at best standing still. Numerous areas of reform are behind based on the Chinese data we highlight, including labor reform as gauged by wage growth for lower-income migrant workers, competition policy, cross-border investment policy, and fiscal policy reform. Five out of ten areas show at best mixed results, with little movement to date (in financial system, state owned enterprise rationalization, trade, land, and environmental reform). Policy movement, a precursor of future outcomes, is often mixed, with continued public displays of policy resolve, but limited fundamental progress on the ground. China‘s 2013 reform program is key to long-term, sustainable economic growth, and if economic reform momentum does not rise, both China’s GDP potential and its contribution to future international economic development will be depleted. Given the accumulated liabilities from past growth choices, current resistance to reform on the ground, and built-in demographic challenges of an aging population, longer-term prospects face increasing headwinds.

Note: The assessment visualized above is the authors’ judgement based on the primary indicators.

Note: The assessment visualized above is the authors’ judgement based on the primary indicators.

The Dashboard Gauges: Primary Indicators

Our primary reform indicators gauge outcomes in China’s economic performance: that is, implementation of Beijing’s reform goals is assessed based primarily on changes we observe in economic data over time. Only one of our quantitative indicators shows significant movement in the right direction this cycle: innovation. As with all our 10 policy performance gauges, our chart on innovation captures outcomes rather than everything that matters. For innovation, we measure the weight of innovative industries as a share of all industrial sector value-added in China. As of midyear 2017, the share of innovative industries continued to rise. This trend started in 2016, although this may have peaked for the time being, as growth leveled off in 2Q2017. At the current pace of adjustment, China will reach U.S. (2014) levels of innovative industry share in total industrial output as soon as 2018 or 2019. However, to lock in a greater role for more advanced technology sectors, Beijing will need to allow sunset industries to shut down rather than step in to resuscitate them as in the past.

Other than the growing share of output from innovative sectors (partly attributable to policies such as Made in China 2025, which are controversial in foreign capitals), our dashboard does not show positive outcomes this quarter. Half of the policy areas we track are unchanged. Our composite index of trade liberalization for high-protection products was flat in the most recent quarter, at virtually the same place it started in 2013. After hopeful noises about restarting state-owned enterprise (SOE) rationalization earlier in the year, our measure of state withdrawal from “normal” industries has so far shown no improvement. In financial system reform, our efficiency measure improved just slightly, and policymakers are leaning in hard to change directions, but the thirst for short-term growth, state-directed credit, and financial stability leans back heavily, leaving the trend in limbo. On the environment, air quality continued a slight improvement trend, but water quality moved slightly backward. And on land reform, inadequate data prevent us from seeing whether several good policy steps announced this year have increased the rate of rural land marketization.

The four remaining reform clusters we track show negative movement this quarter. For competition policy, we watch whether foreign and domestic firms are treated equally in merger reviews. This quarter, the review rate for foreigners went up and for domestic firms it went down, adding to an already persistent gap. On cross-border-investment policy, deteriorating balance-of-payments conditions were stabilized, but at a price to Beijing’s larger goal of a greater role in the global financial system: the ratio of cross-border capital flows to GDP continued at near decade lows of 6% – well below the average levels that existed at the time of the 2013 Third Plenum meetings. As for fiscal policy, the outcome picture got worse, with both standard and augmented measures of local fiscal gaps increasing (the latter in record territory) as local authorities spend to support growth targets and provide essential – but underfunded – social services such as healthcare. Finally, in labor policy, less-protected migrant workers saw the rate of wage growth languish well below GDP growth for the fifth consecutive quarter. This indicates that current growth – even if it is achieving the stated target for the year of 6.5% or greater – is capital intensive, rather than benefitting low-wage workers.

The Policy Picture

Quantitative indicators reflect results so far. A parallel analysis of the policy scene speaks to the outlook. In some, but not all areas, we observe policy moves that could yield reform dividends in the coming quarters. But the predominant political and policy factor in fall 2017 is the just completed 19th National Party Congress. This full Party Congress takes place every five years and results in a new Party Politburo and paramount Standing Committee for the coming five years. This is a Party conclave, not a governmental meeting, but the Party leadership assignments determine governmental outcomes down the line. The common assumption is that jockeying for position at this Congress has stymied economic policy reform this year. This view is shared by most Chinese and foreign observers.

To some degree, this is a misleading assumption. First, policy action in several areas has proceeded despite the Congress, out of necessity. Second, to the extent that reform has bogged down in many areas, delays were evident long before the Congress drew near, and inaction cannot be attributed to short-term political calendar effects. The approaching meetings seem more a convenient excuse for stalled reforms than the cause.

Prevailing narratives also misdirect attention to another argument related to the policy landscape: that only with this Congress will Xi Jinping have consolidated sufficient power to have a free hand to “revive” reforms that he had already endorsed in 2013 but has been prevented from implementing. Xi’s assumption of all major civil, economic, and military leadership roles over the previous five years, including many traditionally delegated to the Premier, indicates that the bulk of power consolidation under Xi has long been accomplished. Blaming an insufficiency of power for the level of progress in implementing the 2013 reform agenda is not persuasive. This is why Chinese officials have not waded into the speculation about the relationship between reform and the Congress.

A real impediment [to reform] is that leaders remain unsure that stability can be maintained while reform is being implemented.

Setting aside theories of Party Congress politics and the pace of power consolidation as being to blame for slow reform, the patchy record of implementation so far remains unexplained. Chinese officials are aware that reform is mission critical for national prosperity and power, so we can set aside the notion that there is no fundamental interest in reform. What is a real impediment is that leaders remain unsure that stability can be maintained while reform is being implemented. Reform is inherently unstable. It has always been this way, as shown by previous periods of reform in the 1980s and 1990s. Reform means intentionally destabilizing aspects of the system as we know it, by design, to make policy durable for the long term. As growth declines, working through this adjustment grows harder with each passing year. Conventional analysis teaches that leaders, even authoritarian ones, are better off commencing reforms early in a political cycle so that adjustment pains are out of the way before jockeying for the next political cycle begins. If this logic applies in China‘s case, then the conclusion of the Party Congress will now make a reform push more likely. However, if the Party thinks China is immune to the forces that have derailed other emerging economies, such as the “middle-income trap,” then this sense of urgency may be missing.

While the Party Congress absorbed most of the attention through the second quarter, some policy changes were already taking place. In financial policy, the People’s Bank successfully steered monetary growth down, arriving at multi-decade lows by midyear. This meant higher interest rates, which are good for disciplining lending and beginning to address long-term debt risks, as well as giving households better returns on savings. This also helped stabilize the capital-output ratio that we watch: if sustained, this trend could anchor positive movement in a number of dimensions going forward.

State-owned enterprise reform received attention, with three debates intersecting in the quarter. First, Beijing has hinted since 2013 at a categorization system clarifying where the state would remain dominant, where it could mix with private investment, and where it would withdraw. By January, provinces gave recommendations on this, but Beijing has declined to announce a national scheme. Second, “mixed ownership” got a concrete face with a new shareholding structure for SOE China Unicom. And third, guidance on governance and the role of the Party in SOEs was rolled out. All central SOEs are to be converted to shareholding corporations by year-end, and the Party’s role is to be spelled out in Articles of Association. This policy movement is promising, though questions remain unanswered. This is happening against the backdrop of supply side reform: production shutdowns in overcapacity sectors such as steel, and forced mergers in order to reduce deflation, waste, financial inefficiency, and trade problems. But one side-effect is to make key SOEs look more profitable, thanks to inflationary side-effects of the reform, which in turn influence the debate over broader reform directions.

Our environmental outcome measure remains indeterminate (air quality up, water quality down), but it became clearer in the quarter that central inspection teams were no joke. These units were taking up residence in provincial capitals for up to a month at a time; with a combination of senior officials, Party discipline agents, and technocrats, they made their presence felt. Their instructions are to cut air pollution (PM2.5) 15% year-on-year October through March (the winter season, when the worst emissions occur due to heating). Rather than environmental outcomes being dependent on the macroeconomic cycle and stimulus, if these policies are enforced then environmental reform could well drive the macro outlook for a change, possibly steering GDP down by spring.

Land reform has been among the slowest moving policy areas in recent years. Land reform is critical both for social and economic reasons, but has gotten low priority. Though our indicators are limited by data shortcomings, land reform policy saw movement this quarter: after a long wait, debate started on Land Management Law revisions – the first since 2004. Officials are taking stock of lessons from pilot programs, though there is not yet consensus on long-term reforms. Rural construction land pilots are modest but positive, and an agricultural land-use rights registration process is moving toward completion. Debate on revisions to the land law, plus conclusion of the Party Congress, are likely to add momentum to a slow process.

The View from Abroad

We are at a critical moment for clarity on China’s reform trend. After years of expecting China to converge with liberal economic norms, many of China’s partners, including the United States, Europe, Britain, and Australia, are debating fundamental shifts in policy. Many are considering actions to offset China’s competitive edge on the grounds that those advantages are unfair and unlikely to be manageable until China reforms. Our Dashboard does show backsliding in areas, though not definitive enough to prove China is in a full retreat from reform and opening. But the problem is not just avoiding retreat, but increasing forward movement. Outcomes are currently insufficient, and signs of policy redirection are unclear. Patience in anticipation of better outcomes has run thin as the stakes begin to rise. There is a case to be made that if China is serious about economic reform, there will never be a better time to restart than now. The first full quarterly indicators of post-Congress performance will not be available until spring. Until then, policy interpretation will play an outsized role until the acid test of outcome data becomes available.